As a new academic year begins, student flows between the U.S. and China remain far below pre-Covid levels of 2019-2020, while lingering issues and tense U.S.-China relations cloud the prospects for resuming robust two-way educational exchanges in the near future. In this uncertain period, the US-China Education Trust is proud to announce the release of Three Decades of Chinese Students in America, 1991-2021. This joint report from USCET and the China Data Lab of the UC San Diego 21st Century China Center provides a broad perspective on the changing composition and experiences of students from China who earned degrees in the United States over a period of three decades.[i]

Why Survey Former Chinese Students?

The estimated three million students from China who have studied in the United States since the late 1970s represent one of the largest cross-border flows of students in modern times, and they have long been viewed as a generally positive presence at American colleges and universities. In recent years however, Chinese international students have become a focal point of rising U.S.-China tensions and suspicions on all sides, with some viewing the students as insidious agents of Chinese government influence and others raising doubts about their loyalty to China. As critics continue to raise questions about the value of educating students from China in America, it is important to consider the long-term costs and benefits of this exchange. USCET launched a survey of former Chinese students in America in late 2022 to create a wider framework for understanding this group, add student perspectives to a dialogue that often takes place without their input, and put a human face on the stereotypes and statistics.

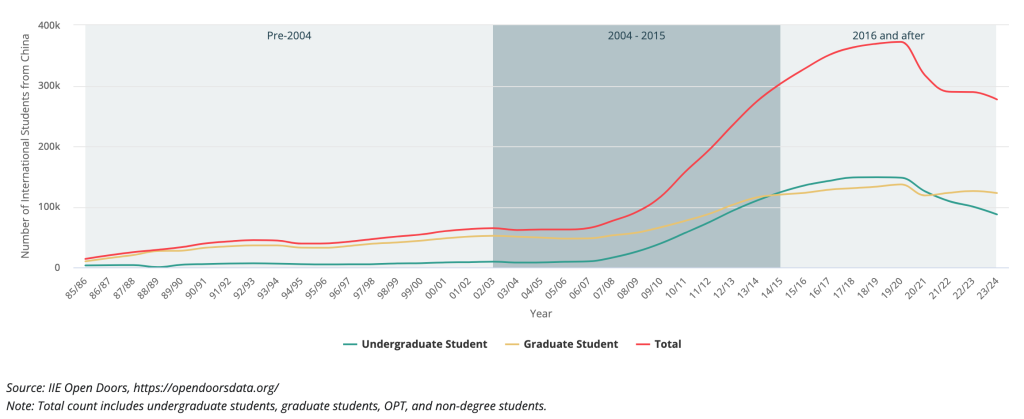

The survey is, to our knowledge, unique in its broad scope and timeframe. While most studies focus on current students from China or recent graduates from particular schools or regions, this survey spans three decades and includes undergraduate and graduate alumni who attended universities across the country. Respondents were divided into three cohorts based on larger societal trends impacting the composition of the group. The first cohort consisted largely of graduate students pursuing advanced degrees at U.S. institutions between 1991 and 2003. The second cohort graduated between 2004 and 2015, a time when the number of Chinese international students rose steeply and undergraduates surpassed graduate students in number. The third cohort completed degrees in the U.S. between 2016 and 2021. During this period, tensions between the two nations rose steadily and the pandemic temporarily all but halted student flows. The annual increases in Chinese international student numbers slowed and then reversed during these last years.

Chinese International Students in America 1985-2023

Challenges and Questions

The tense and unsettled state of U.S.-China relations made this a difficult time to conduct a survey of former Chinese students, even a strictly anonymous one as this was. Students from China have been criticized in the U.S. as potential spies, and in China as too influenced by the West. The resulting political whiplash may well have depressed the number of former Chinese international students willing to fill out a survey, particularly, the relatively recent graduates who have been the most directly impacted by the downturn in relations. The survey results represent a sample of 404 former students from China, a small segment of the former Chinese student population but one whose responses track with known trends in the larger student population.

The broad scope of the survey allowed us to gather a range of experiences and compare responses over time among different segments of the population, although it obscured the impact of events of shorter duration. It did not account for the effect of pandemic restrictions, for example, although many 2020 and 2021 graduates at the tail end of our survey’s time frame had to study remotely from China during their final semesters. Balancing the number of responses from various segments of the population presented another challenge. We achieved good representation in terms of gender, cohort, type of institution, and country of citizenship but were less successful in terms of degrees pursued, receiving far more responses from graduate students than undergraduates. Another imbalance was the fact that 77 percent of our respondents currently reside in the United States, although not all are Americans; some 58 percent of the respondents overall are Chinese citizens. The preponderance of U.S.-based respondents was not unexpected since it proved to be relatively difficult to attract survey takers residing in China, but it implies that our conclusions apply more to those individuals with the desire or opportunity to remain in the U.S., whether they are Chinese or American citizens. The Methodology section of the report discusses these issues in more detail.

These limitations were accepted in the interest of applying a wide lens to the topic. The goal of this survey was not only to add to our understanding of Chinese student experiences in America, but to stimulate dialogue and raise questions for further research. How, for example, can American colleges and universities successfully engage Chinese international students in campus life and make sure they understand their academic rights and responsibilities? What steps can be taken to minimize political pressures that surround these students in times of tense U.S.-China relations? What benefits and risks are associated with the presence of Chinese international students on campus over the long term and how can they be measured?

Key Survey Findings

The full online survey report is divided into four broad questions related to the student experience. Each question is answered with visual data, analysis, and key takeaways. The findings are briefly summarized below and the full analysis can be accessed by clicking on each question in blue.

The vast majority of survey respondents unequivocally reported that they came to the United States in search of excellence in education. Not surprisingly, other top motivating factors included the chance to experience life in another country, greater freedom in choosing what to study, and the opportunity to improve career prospects. As China developed a sizable middle class, more Chinese families were able to afford to send students to study abroad. Less than 10 percent of our sample received financial support from their families prior to 2004, rising to more than 75 percent of those who graduated after 2015. Almost two-thirds received merit-based financial assistance from their schools, and less than 2 percent reported receiving Chinese government funding.

Although employment was the most common nonacademic use of student time, a third of respondents also participated in sports at some level and in many other extracurricular activities at lower rates. However, survey takers in the later cohorts reported increasing academic pressure and less time for social activities. Looking at media consumption as another measure of campus integration, students got their outside news from sources that changed over time as one would expect. Newspapers and TV were supplanted by significant increases in the use of both Chinese and American social media. The survey also provides some evidence to counter the notion that students from China have relied mainly on Chinese media sources while in America – respondents used both American and Chinese sources at high rates, showing a great deal of integration into the American media environment.

What type of negative experiences have Chinese students encountered on campus?

Chinese international students are clearly affected by changes in U.S.-China relations and domestic politics in both countries. Not surprisingly, our survey shows a rise in students reporting uncomfortable pressure to conform to certain political views over the years, with this pressure emanating from both American and Chinese sources. Those who graduated before 2004 reported relatively little intrusion of politics into their years of study, but such concerns rose significantly for the group that graduated after 2015. Incidents involving anti-Asian sentiments and perceived discrimination also rose uncomfortably over time.

How do former Chinese students feel about their time studying in America?

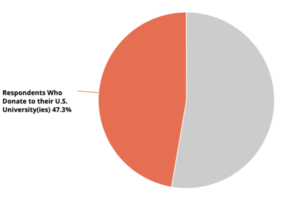

Despite negative incidents, signs of durable goodwill were not hard to find among the survey respondents. Most looked back on their school experience with warm feelings for their campus and their friends, as well as the people and landmarks they encountered through travel. More than 85 percent of the sample reported that they found Americans friendly and welcoming, and a similar percent said they would choose to study in America again if given the choice now. Significantly, many respondents remain connected to their school in some way – the rate of participation in American alumni associations and of financial giving to their schools both exceeded the US average by a wide margin.

In keeping with the lower average age of the Chinese international student population over time and rising tension in U.S.-China relations, there was a drop in the number of students who stayed on to become U.S. citizens over the decades – from 71 percent in the first cohort of 1991-2004 graduates to 30 percent in the second cohort. The third cohort of 2016-2021 graduates left school too recently to determine ultimate citizenship, although a growing number of this group report that they tried but failed to stay in the U.S. after graduation.

Closing Thoughts

Overall, these survey results appear to be reassuring for Americans worried about the presence of students from China. Our sample shows a group making their own decisions to study in America, largely motivated by a desire for academic excellence and personal gain, primarily financed by family and university support. Despite some feelings of alienation and negative political or racial encounters on campus, most respondents report that they took away fond memories and enduring friendships, and many have chosen to stay in touch with their university.

At the US-China Education Trust, we believe educational exchanges form the bedrock of U.S.-China relations and are a critical element in maintaining peace between our two countries. Exchanging students and scholars was a top priority when the U.S. and China normalized relations in the1970s, and has remained a mainstay of people-to-people relations ever since. We hope that both countries will continue to welcome each other’s students and provide ample opportunities for them to engage with each other’s societies first-hand. This is more important than ever during unsettled periods in U.S.-China relations in order to ensure that our future leaders can communicate with each other, understand cultural nuances, and work their way together through difficult bilateral issues and geopolitical challenges.

The US-China Education Trust is grateful to the Henry Luce Foundation for their support of this project and to the team from UCSD’s China Data Lab for their critical role in the project. Members of the China Data Lab at UC San Diego’s 21st Century China Center consulted on the project, analyzed the survey data, co-authored the full Survey Report, and host it on their website. It is our shared hope that the initial findings in this report will raise new questions, elevate student voices, stimulate dialogue, and encourage further research. Special thanks to USCET’s former program manager, Trenton Marsolek, who worked tirelessly on managing all aspects of the USCET survey.

We would like to thank the many individuals who took the survey and shared it with their former classmates, and the dozens of other individuals and organizations not themselves eligible to take part in the survey who provided support and shared the survey widely. A list of supporting organizations is found in the Methodology section.

[i] In this report the terms “Chinese students” and “Chinese international students” refer exclusively to students from the P.R.C.